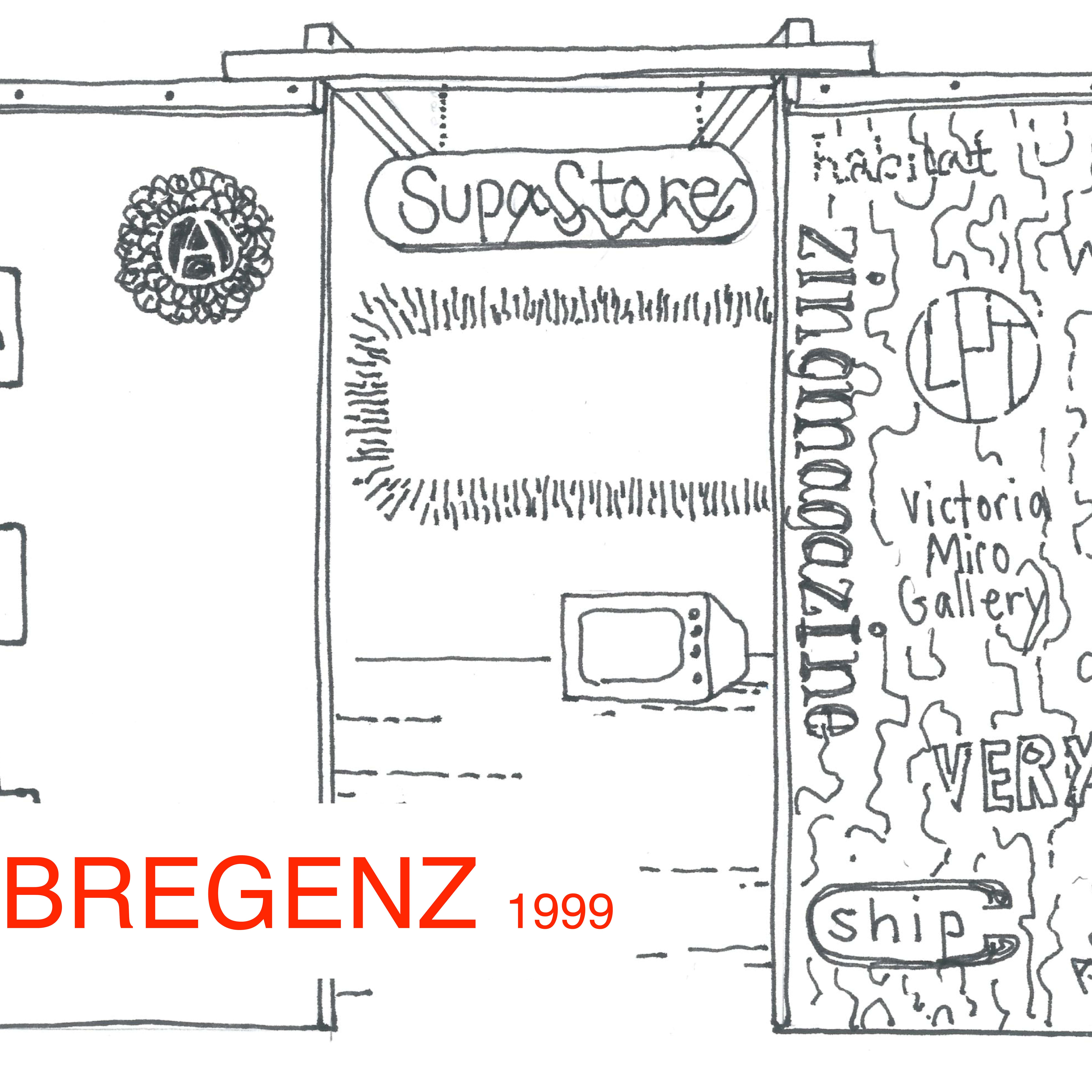

SupaStore est.1993

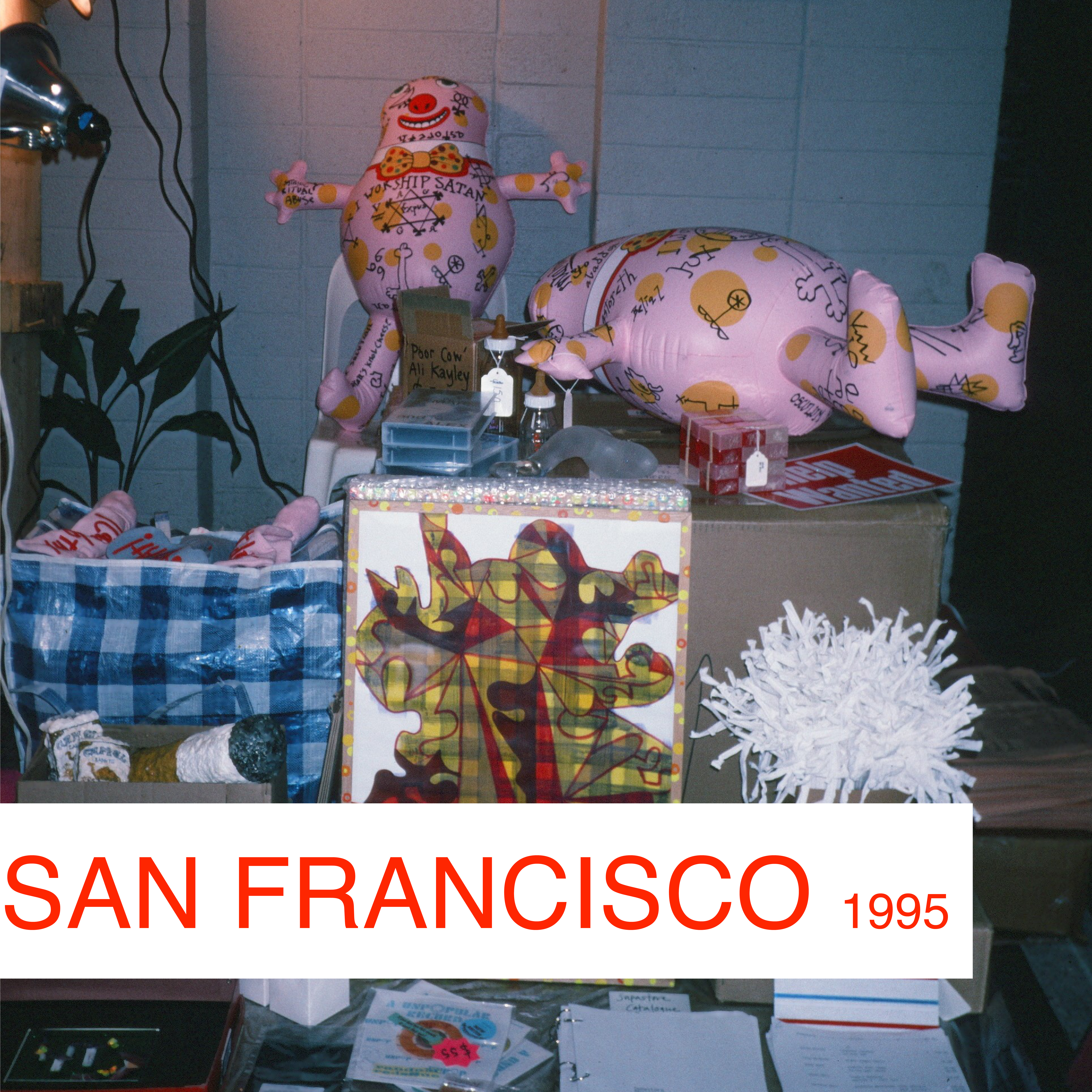

SupaStore is a durational artwork conceived and curated by Sarah Staton. Acting as impresario and participant, Staton uses her position as an artist to invite friends, peers and heroes to put up art works for sale in a hybrid composite of gallery and shop. Initiated through early iterations in London (1993-), the work has since that time been produced, responsively, in a schedule of variations determined by the geographic and cultural specificities associated with successive hosts and locales.

SupaStore uses the language and visual conventions of product and graphic design, architecture, art and shopping to create a heavily codified yet indeterminate space where – in a spirit of levity, pop and play – art’s autonomy is lost, and lost again. As it negotiates its fate of proximity to the commodity, conditions of objecthood and reproducibility are shown to be irrepressible for them both, equally so the capacities of aesthesis/seduction and misdirection/deceit.

Editioned, stacked, hung, priced and labelled, in SupaStore art is prone to democratise and ‘pop up’ – using language and materials with an ever-diminishing sense of etiquette. It skirts but belittles the probity of serious institutional behaviours as these are expected from unique art works in the museum (a latent space to which SupaStore gestures, ambivalently, from its position of debtor and joker combined). In a seemingly endless array of ply-veneered closets, boxes, niches, corners, art reproduces itself as a branded, laughing, uncanny thing from London’s Charing Cross Road, Foley Street and The Mall, to the hotels and art galleries of San Francisco, Middlesborough, New York, and Norwich.

On the eve of the internet’s explosion into public consciousness, SupaStore’s first incarnation partook of a fascination with the network and ‘networking’ much in evidence during the nineties – as was demonstrated in comparable projects, such as Matthew Higgs’ publishing project Seven Wonders of the World (Bookworks, 1999). Both perform their function self-reflexively, using a distribution vehicle to accumulate names (the artist’s identifying label) that are then cohered together – webbed, we might say, in keeping with the times – through the somewhat mysterious soft power and socialised knowledge provided by an invited group of art aficionados (or, in Staton’s case, by the artist-shopkeeper herself).

SupaStore’s kinship with the internet is all of a piece with its other, dominant cultural inflections: Staton’s preoccupation with language and circulation is, for example, conspicuously Americanised. This is a ‘store’, not a ‘shop’; it is ‘supa’, not ‘super’. The artistic legacies which most obviously suffuse the working model are those of Warhol, Johns, Oldenburg, Wiener: brash, impatient, cutting to the chase, and not fixated on nuance, detail or a decorum of scale. If SupaStore was an apprentice, it would be to the delirious master practices of Rem Koolhaas – and his fetishisation of lifts and escalators – less so the subversive, speculative practices of Archigram et. al. But this is perhaps only to acknowledge the mutual imbrication of the pop practices its author was surrounded by during the artistically formative moment of the early nineties – when Sarah Lucas and Tracey Emin famously also opened their ‘The Shop’ (1992) in London’s East End – and to posit British art as always the tricksterish interlocutor between American and European traditions and legacies. Hence, SupaStore is as much the child of David Hammons’ snowballs,* as it is of Marcel Duchamp photoreliefs, sold at the Concours Lépine inventor's fair of 1935.* Like the Walter Benjamin essay on reproducibility, media and aura that is its most lasting inspiration, [ref]* this means it is coloured in equal measure by the melancholy of tragic loss as it is by a bloody-minded insistence on hope and egalitarianism, as we might direct these at the most unlikely objects of capitalist society.

The SupaStore website is due to launch in the winter of 2024.